Our latest excursion to investigate the local waterways saw us head to Stony Creek in the Brisbane Ranges over the weekend. We started from the Stony Creek Picnic Ground - having previously walked most of the section of track from Anakie Gorge up Stony Creek - and followed the Ted Errey Nature Circuit. The late Ted Errey, I discover was the president of the Geelong Field Naturalists Club and a keen advocate of the national park.

We followed the path up a spur to the high points overlooking the gorge below and from various lookouts interspersed along the track, we could see Mt Anakie and away towards Corio Bay, extensive views of the Brisbane Ranges which are still recovering from the 2006 bushfires and the Lower Stony Creek Reservoir.

|

| Ted Errey track showing regrowth after bushfire damage |

This latter structure forms part of Geelong's water supply and is in part the reason I can justify including the Brisbane Ranges and Stony Creek in my Barwon Blog. Whilst the creek is not a tributary of the Moorabool River - it discharges into Little River - water from the east branch of the Moorabool River is diverted in to the Stony Creek Reservoirs for transfer to Geelong.

So, how does it all work?

In 1841, as I have blogged previously, Captain Foster Fyans had the breakwater constructed across the Barwon to improve Geelong's water supply, however by the 1860s the supply from the Barwon was both inadequate for the town's needs and was polluted by the local industry.

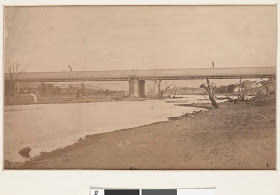

|

View across Brisbane Ranges with Lower Stony Creek

Reservoir in the middle distance |

It was decided that a new, more reliable water source was required. So, to cut a long story slightly shorter, after the expected political wrangling and corner cutting, a dam was built across Stony Creek in the Brisbane Ranges. This initial earthen wall dam (Stony Creek Reservoir 1) was completed in 1873, but some subsidence in the dam wall meant it would have a smaller capacity than anticipated, so the Lower Stony Creek Reservoir was built further down the creek - with a concrete wall - between 1873 and 1874. From the upper reservoir, water was sent via an aqueduct to the Anakie Pipe Head Basin and from the lower reservoir via a pipe running beneath Anakie Gorge to a point below the basin. From here, the water was distributed to Geelong via storage basins at Lovely Banks and Montpellier.

|

Decommissioned waterpipe from the Lower Stony

Creek Reservoir, exiting a tunnel and crossing the creek.

The pipes were originally constructed from timber |

By the turn of the 20th century however, even these measures were inadequate for Geelong's water needs, so a diversion weir - the Bolwarrah Weir I believe - was built on the East Moorabool River. The weir was designed to raise the water level of the river at this point allowing some of the flow to be diverted into a channel - the Ballan Channel - which then carried water to the Upper Stony Creek Reservoir.

As Geelong continued to grow, more water was needed and over the years, much of this continued to be drawn from the Moorabool River. Water first flowed into the Koorweingaboora Reservoir located upstream of Bolwarrah Weir near the headwaters of the Moorabool East Branch in 1911, then in 1914 and 1918 the Upper Stony Creek Reservoirs 2 and 3 respectively were completed. In 1940, the capacity of the Ballan Channel was doubled to allow more water to be drawn from the upper reaches of the Moorabool East Branch and by 1954 the Bostock Reservoir, located on the Moorabool East Branch just outside Ballan and below the Bolwarrah Weir, came on line. It is also connected to the Ballan Channel via its own open channel - the Bostock Channel.

But that is not the end of the story. Along the west branch of the Moorabool River are two significant reservoirs. The Moorabool Reservoir was built near the headwaters of the Moorabool West Branch in 1915, then, in 1972 the Bungal Dam was built at Lal Lal. This latter reservoir at the time it was built was equivalent in volume to Geelong's total water storage.

Most recently in 1999, the pipes and the channel which for so many years carried water from the Stony Creek Reservoirs to the basin at Anakie were decommissioned and replaced by a pipe running along the Steiglitz-Durdidwarrah Road. In total about one third of the water taken from the Moorabool River system is available to Geelong with the remainder being used by Ballarat. This accounts for approximately one fifth of Geelong's water requirements. The remainder is supplied by the Barwon River system and in more recent years by borefields at Barwon Downs and Anglesea.

Phew! So, back to our walk. In some places the track was rocky and only vaguely defined, although the blue trail markers helped keep us on course. In other places we were walking along access tracks which were broad and reasonably level.

|

| Rocky section of the Ted Errey Track |

We reached the summit, took in the views, snapped some shots and continued on our way, however a little under half way in, we were informed that the Ted Errey Trail beyond Switch Road was closed. Being the intrepid adventurers we are - and having ignored such signs before with no noticeable ill effects - we decided to soldier on. All was well as we crested the rise and headed down the steep, rocky slope which took us back to the bottom of Anakie Gorge, to connect with the trail which ran along beside the creek. We were within 2km of reaching our goal when we came across our first obstacle. A small weir which I'm sure we walked across on a previous occasion, was now under a small amount of water.

|

| The one flooded weir we didn't need to cross |

Hmmm... never mind, we could remove our shoes and cross without too much trouble. This we did. Problem solved - until we came to the next point where the path crossed the creek. There was a bridge, but it was on its side, somewhere downstream of where it should have been. Again, the creek wasn't too deep or wide, but the thought of having to deal with the shoes again didn't appeal, so we resigned ourselves to getting wet feet and plunged across. Once again we all made the opposite bank without having to fish any children out from some point downstream.

|

| Yet another creek crossing |

Done! Now to finish our walk! That was, until we reached another point where the path crossed the creek - a second submerged weir - and another, and another and another. In all, we crossed the creek seven times. On six occasions we were confronted either with no bridge, a submerged weir or a missing bridge. I guess they meant it this time when they said the track was out of action! However, we did finally make it back to our starting point and within the specified time frame.

And so, we squelched our way to the car and headed for home.

|

Plaque at Montpellier Basin commemorating the centenary of

reticulated water in Geelong |